Finding Hilda: The Story of Three Sisters

/by Emma Friedlander*

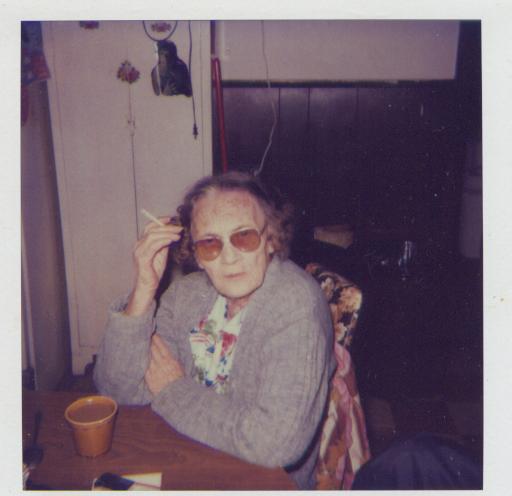

Hilda "Cornell" Roisi in the 1940s, two decades after her time at the Training School for Girls.

During the summer of 2017, I had the privilege of delving into a remarkable story about a group of sisters whose efforts to understand the complicated life of their grandmother led them to contact the Prison Public Memory Project. Their grandmother, Hilda, had been incarcerated at the New York State Training School for Girls in Hudson, NY, a fact she had not shared with her family, but was revealed by a census record after her death. I interviewed one of the sisters for this story, reviewed their extensive research findings and did my own historical research to try and confirm and provide context for certain details shared with me. Two of the sisters also graciously fact-checked the story below. While I just had a few weeks to research and write about this family during my internship with the Prison Public Memory Project, I hope that what follows gives readers an understanding of how important it is today that information on people incarcerated in the past be made available and accessible to their descendants. I also hope that what I have written will help to generate more clues for this family’s continuing search for information. If you have information that might be helpful for that purpose, please contact the Prison Public Memory Project at: https://www.prisonpublicmemory.org/contact/

Dawn Patanella always had a special bond with her grandmother. Growing up, Dawn’s mother would drop Dawn off to stay with Grandma Hilda for stretches of time, as her other daughter Lynn had heart problems and Dawn’s mother had her hands full. During that time Dawn required weekly allergy shots, and Hilda often accompanied her to those appointments. Hilda sometimes brought Dawn along to her factory job, which Dawn always found very cool. For fun they would ride around on the city buses in Rochester, NY or on the Midtown Plaza Monorail.

As Dawn grew up, she started hearing nasty rumors about Hilda from her family members. They said that Hilda’s first husband owned brothels and that she had been one of his prostitutes. They said that the reason Hilda moved so frequently was because she made enemies with the neighbors wherever she went. In her later years, she moved frequently among her daughters’ houses, always leaving chaos in her wake and speaking badly about other relatives.

“I thought Grandma walked on water,” Dawn recalled over the phone. “A lot of things that my parents and my aunts and uncles said about Grandma, I didn’t believe them. I didn’t believe any of them until we started doing this research.”

After her grandmother passed away, Dawn came across a 1920 census that listed fifteen-year-old Hilda Cornell as “inmate” at the New York State Training School for Girls in Hudson, New York, a reformatory for “incorrigible” adolescent girls that was once the largest such institution in the United States. Dawn was shocked. Neither she nor her twin sisters Autumn and Lynn with whom she was researching their family history, had any idea that Hilda had been incarcerated as a teenager. Beyond her initial surprise, however, Dawn also recognized the discovery as an entryway into understanding her grandmother’s past. She was one step closer to understanding what made Hilda, known for her blunt tongue, distrust of men, and fierce independence, the way she was.

Researching the Family

Dawn, Autumn, and Lynn started researching their family history around the year 2000. They were curious about their maternal grandfather, who had been in their mother’s life for only a few years and about whom they knew very little. As they fleshed out the various branches of their family tree, they realized that they needed more information about their Grandma Hilda and her large family. This new line of inquiry brought them to that 1920 census, leading their investigation in an entirely new direction. After confirming that the Hilda Cornell listed on the census was indeed their grandmother by cross-referencing the census with a 1919 newspaper article about her arrest for being incorrigible and ungovernable, the sisters dedicated themselves to finding more about Hilda’s time in prison.

The next step in their search brought the sisters to the New York State Archives in Albany, which preserves the State’s government agency records and holds many existing records from the New York State Training School for Girls. For twins Lynn and Autumn’s birthday on November 9, 2004, the sisters’ father bought them a round-trip bus ticket from their home in Western New York to Albany. Despite only spending a couple of hours at the State Archives during that first trip, the twins found an encouraging amount of information about Hilda, including her commitment record.

“They were so excited when they came home,” Dawn remembered of that initial archives visit. “They said, ‘Oh my god! Oh my god! Look what we found!’”

Since they first began their search, Dawn, Autumn, and Lynn have filled out a sizable amount of their grandmother’s story. They know from her commitment record that she was first arrested on January 14, 1919 for being “incorrigible and ungovernable.”

They know that she soon violated her parole and was arrested again in March of 1919, and finally sent to the Training School on May 17, 1919. For information about Hilda’s time at the prison, the Training School’s parole records have been the most helpful source. These records state that “Hilda has an uncertain disposition, at times is very silly at other times stubborn and disagreeable, becomes easily discouraged, always chooses most doubtful girls as companions.” The records detail the three times she was paroled, each time to work as a maid in the home of a different New York family, which sent her from Hudson to the Catskills to her future home in Rochester. On her third discharge, according to the parole book, Hilda ran away. That was in April of 1923, four years after Hilda had originally come to the youth prison. The following year she gave birth to her first child.

Although Dawn was surprised to learn about her grandmother’s atypical past, the revelation did not change the loving memory she had of Hilda. In fact, learning the truth of Hilda’s difficult upbringing, her time in prison, and how that experience subsequently shaped her life has allowed Dawn to better understand and appreciate Hilda’s complicated character.

“It made us realize that the reasons why she was like she was were because of not only her upbringing, but also because of being in the institution,” Dawn said. “Then we understood how her life was after the institution, and the things that she fell into.”

Reforming the Incorrigible

As was often the case for girls incarcerated at the Training School, no particular crime led to Hilda’s commitment. Instead she was charged as “incorrigible and ungovernable,” a catchall term for girls who did not conform to the societal norms of the day and or lived in an impoverished environment. Dawn and her sisters have located certain details of the difficult conditions under which their grandmother grew up. Of Hilda and her six siblings, at least four (possibly more) spent time in institutions. Her mother, Sarah, died when Hilda was only twelve. The story, rumored in the family, goes that the children placed their mother’s body in a wheelbarrow and rolled her into town to the coroner’s office. They say that the father, Delos, known for his drinking habit, was nowhere to be found.

Historical record confirms that Delos remarried only a few months later, and his new wife along with two of her children moved in with the Cornells. Dawn remembers Hilda talking about when her stepmother and stepsiblings moved in. According to Hilda, her stepsiblings were fed and cared for far better than Hilda and her siblings, who were largely left to fend for themselves. Family members have also reported that Hilda was molested by relatives.

Although it is impossible to confirm the validity of each of these details, they nonetheless give an overall impression of Hilda’s troubled upbringing. Dawn was then able to understand that Hilda’s commitment at the Training School for Girls was not due to one particular vice or crime on Hilda’s part, but instead the result of complex external factors. In many ways, the state’s institutionalization of Hilda likely aimed not only to reform her character, but also to protect her from a dysfunctional home environment.

Investigating the Rumors

Moreover, the details of Hilda’s institutionalization, especially her three separate paroles, have helped Dawn piece together periods of Hilda’s life that she had before only heard rumors about.

“She talked about the Catskills, and we never knew where the Catskills came from. Why was she over by the Catskills?” Dawn said. “Obviously, one place she was sent to was basically in the Catskills. ‘The House in the Woods.’”

Dawn’s parole records reveal that her second parole was to service a Mrs. G Smith, whose husband owned a lodge called “The House in the Woods” in the Catskills. Dawn and her sisters learned that after a certain amount of time at the Training School, the girls were placed on parole to work at family homes and businesses in the region. Hilda’s three separate entries in the parole book explain why their grandmother popped up in so many different locales throughout the early 1920s, including the Catskills, which is where she likely met her first husband, who ran brothels in the region.

For her third parole, Hilda was sent to work for Mrs. R. G. Slattery in Rochester. A few months later she was transferred to a different family in Rochester, the McKelveys, in January of 1923. The record shows that after three months working for the McKelveys, she ran away. Hilda’s escape appears to have been successful, for her record at the Training School there ends. Within the following year, Hilda gave birth to her first child in Rochester.

Although Dawn, Autumn, and Lynn have pieced together the most pivotal moments of Hilda’s time at the Training School, historical record is not always so explicit. Where specific details about Hilda are missing, the sisters have been able to pull from other sources in order to flesh out a picture of what her life was like.

The Progressive Era

Much of this information can be garnered from the Training School’s Annual Reports. These reports, which included commentary by the Board of Managers, Superintendent, and other staff, provide statistical and biographical information about the girls at the school during that year, as well as information about any major events or developments that may have occurred. The reports reveal that conduct at the Training School changed drastically from when Hilda arrived in 1919 to when she left in 1923. In 1919 the Superintendent was Hortense Bruce, a woman condemned by the New York Department of Efficiency and Economy (NYDEE) four years earlier for her repressive disciplinary measures. After the NYDEE report was released, the Board of Managers at the Training School heavily defended Bruce. They released a counter-report that explained that disciplinary measures were necessary to reform incorrigible young women, who were more prone to “uncontrolled, nervous outbreaks” than their male counterparts. When Hilda arrived, Hortense Bruce’s strict disciplinary measures were still in practice. These disciplinary measures, according to a report by the Board of Managers, included washing girls’ mouths out with bitter tonic, plastering their lips shut, cuffing their hands and legs, and lengthy periods of solitary confinement.

By the time Hilda left the Training School, the Progressive Era had begun in the United States and reforms were introduced to the institution. Dr. Hortense Bruce retired in 1922, succeeded briefly by board member Mary Hinkley and then more permanently by Fannie French Morse, a progressive leader in juvenile reform who viewed delinquency as the result of social inequity rather than biological factors. Morse believed that girls were reformed through programs of farming and vocational training that prevented idleness, and not by harsh disciplinary measures. As Hilda was already paroled by the time Morse stepped in, it is uncertain whether she experienced these reforms firsthand. Nonetheless, the period during which Hilda was incarcerated at the Training School proved to be a turning point, leading to significant changes at the Hudson Girls Training School.

Hitting – and Breaking – Walls

Since Dawn, Autumn, and Lynn began their search for their family’s story seventeen years ago, they have uncovered an astonishing number of facts, rumors, and anecdotes. They have located institutional records, photographs, and cousins they never knew existed. From time to time they also struggle, working tirelessly to locate information that may not even exist. However, their search is far from over.

“We hit walls,” Dawn said. “There are times when I’ve been online for two days and haven’t found anything, which can be a little bit discouraging. But then we just put it aside for a couple of weeks and pick back up, and then you find something.”

In fact, Dawn revealed that the secret to her inexhaustible motivation is reliance on always uncovering new bits of information about Grandma Hilda, however small they may be.

“You always find something new, even if it’s just a little bit: ‘Oh my god, she lived here for this amount of time.’ It’s still new information, so it keeps you going.”

For example, Dawn is now focused on finding out more information about a recently discovered distant cousin of Hilda’s named Lavina Rosier, who was kept at the Training School for Girls at the same time as Hilda. She hopes that following this new trail might reveal more information about Hilda’s own life in the institution. Dawn is also constantly on the lookout for photographs of Hilda and her family members, which help to, quite literally, complete the picture of Hilda’s fascinating life.

“We are still looking,” Dawn concluded. “We’re probably going to be searching this until the day we die.”

Hilda at her birthday in 1957.

*Emma Friedlander is an intern with the Prison Public Memory Project in Hudson, NY focusing on research, story development, community engagement and outreach. She is a rising senior at Grinnell College, where she studies History and Russian. Her work experience includes internships at Macmillan Publishers and the Museum at Eldridge Street in New York City. Emma is also the editor-in-chief of the Grinnell College student newspaper, the Scarlet & Black.